|

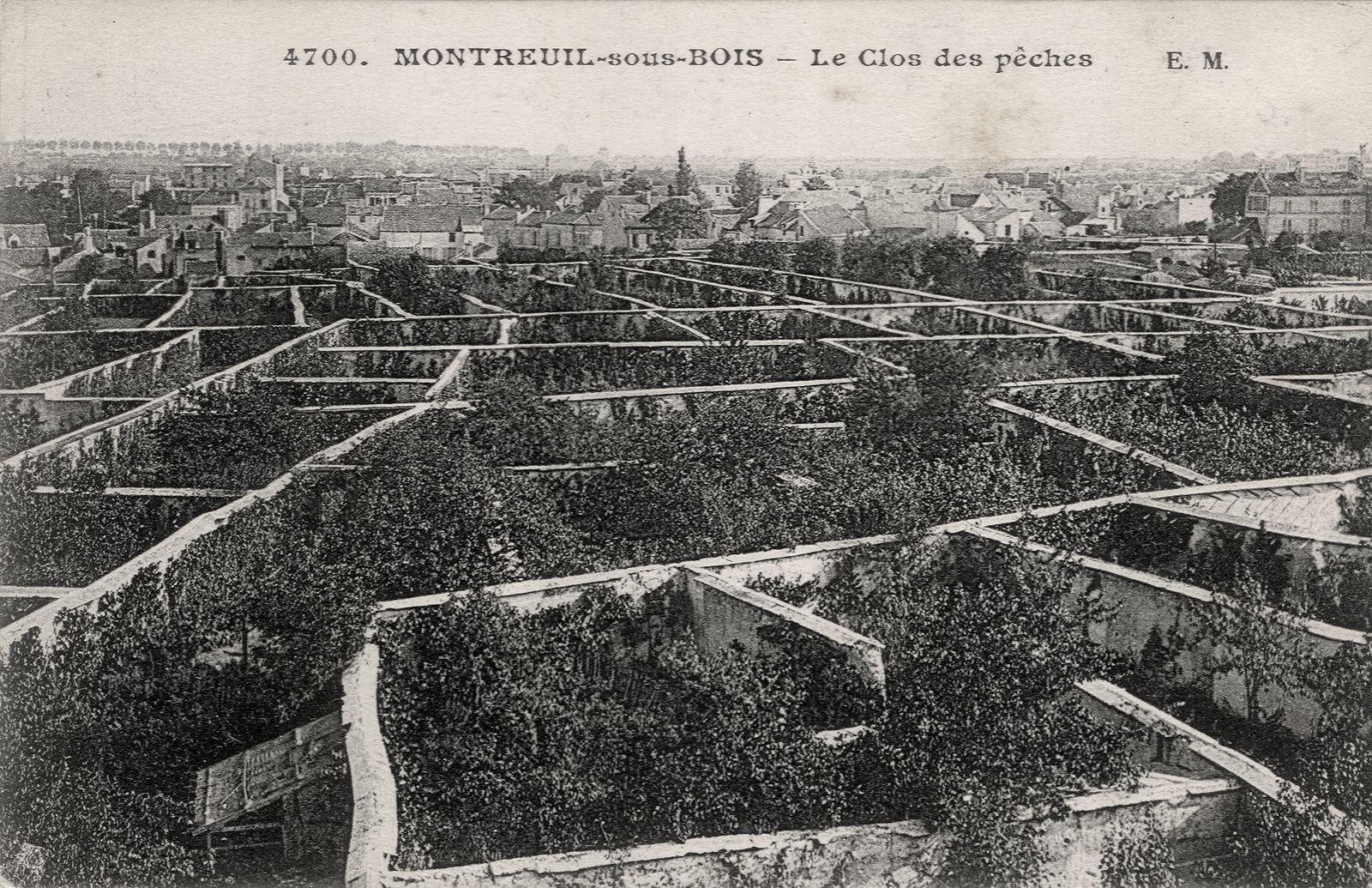

| “Murs à pêches” in Montreuil near Paris |

Increasing the temperature during the winter to provide an all-year round growing season may be possible with mesh cages or canopies to prevent loss of long-wave radiation during winter nights, in conjunction with passive heat storage in heat sinks made of stone, tyres or water reservoirs.

In Montreuil, near Paris, a system of small agricultural plots, aligned north to south and surrounded by 2.7-metre-high, plaster-coated stone walls called “murs à pêches” was created in the 17th Century to grow peaches for the French court. The south-facing walls heated during the day and emitted warmth during the night, allowing peaches, a Mediterranean plant, to be grown in large quantities in a temperate climate. The system was able to raise the local temperature by between 8 and 12°C.

Water and other reflective surface can be used to redirect low winter light. In Rjukan, Norway, and Viganella, Italy deep valleys have been illuminated in winter with the use of mirrors that track the sun and reflect light downwards.